Resources & Tools

Resources and Tools

View All

This risk assessment audit tool includes a template for long-term care, home care and community health support, and non-clinical areas.

Files Attached

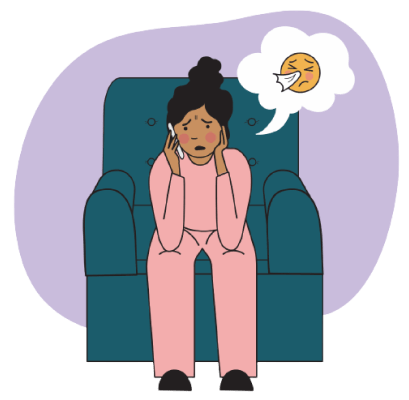

This safety huddle will help you develop a Bullying and harassment policy for your organization.

Files Attached

Training & Education

Training and Education

View All

Programs & Services

Programs and Services

View All

Register

Leading from the Inside Out

- "This program is great and well facilitated. I hope that more healthcare leaders can have the opportunity to participate in this kind of program."

- "This is a good program and especially helpful to have other participants in the same field of work."

- "I thought Callie did a great job at providing opportunities for everyone in the group to open, honest and to share their valuable experiences with others."

- "Working with the other leaders was the most rewarding – to hear other leaders and their struggles and together coming up with self-care strategies to better cope with work-life balance"

Guidelines & Regulations

Guidelines and Regulations

View All

WorkSafeBC’s healthcare and social services planned inspection initiative focuses on high-risk activities in the workplace that lead to serious injuries and time-loss claims.

View News StoryNews Story

WorkSafeBC wants your feedback | Proposed changes to compensation calculations

January 24, 2024

WorkSafeBC is releasing a discussion paper with proposed amendments to the Current Rehabilitation Services and Claims Manual that guide wage rate decisions related to short-term and long-term disability compensation. Recommended amendments include: These changes may affect your claims costs. Click here to view the proposed changes and offer feedback to WorkSafeBC – The deadline is 4:30 p.m. on Friday, […]

View News StoryGuidelines and Regulations

Regulatory News